The lines on Mama Khadijat’s 60-year-old face tell a story of decades spent selling grains, of sacrifices made, and now, of digital betrayal. Just two months ago, her grandson, Musa, had carefully guided her through the setup of a new mobile bank app, promising convenience. Then came the calls.

A smooth voice belonging to “Mr. Halidu” spoke fluent Hausa, urging her to “confirm” bank details for a small government grant. Alone, with Musa away for work and unreachable in Minna, Mama Khadijat, whose formal education ended too soon to read properly, felt a growing unease. That unease turned to trust when a young man with a polite smile and a “government agent” badge knocked on her door one Sunday afternoon. He spoke of a “system error,” assuring her he could fix it right there. She handed over her phone. She confirmed the numbers.

Hours later, her entire life savings, painstakingly accumulated from years of selling rice and guinea corn, vanished.

Mama Khadijat’s story is replicated across Nigeria’s rural areas. Personal data is being harvested, not from faceless digital servers, but directly from the very hands of vulnerable, trusting people.

While cities like Lagos champion AI-driven solutions and a cashless society, the raw materials for this digital future, including the personal data of millions, are being siphoned off. A legal framework, the Nigeria Data Protection Act (NDPA) of 2023, exists to safeguard privacy. Despite this, in the rural communities where most Nigerians live, its practical enforcement leaves much to be desired. Sensitive information, from fingerprints to financial details, flows out to fuel a shadow foreign economy with negative consequences for national sovereignty.

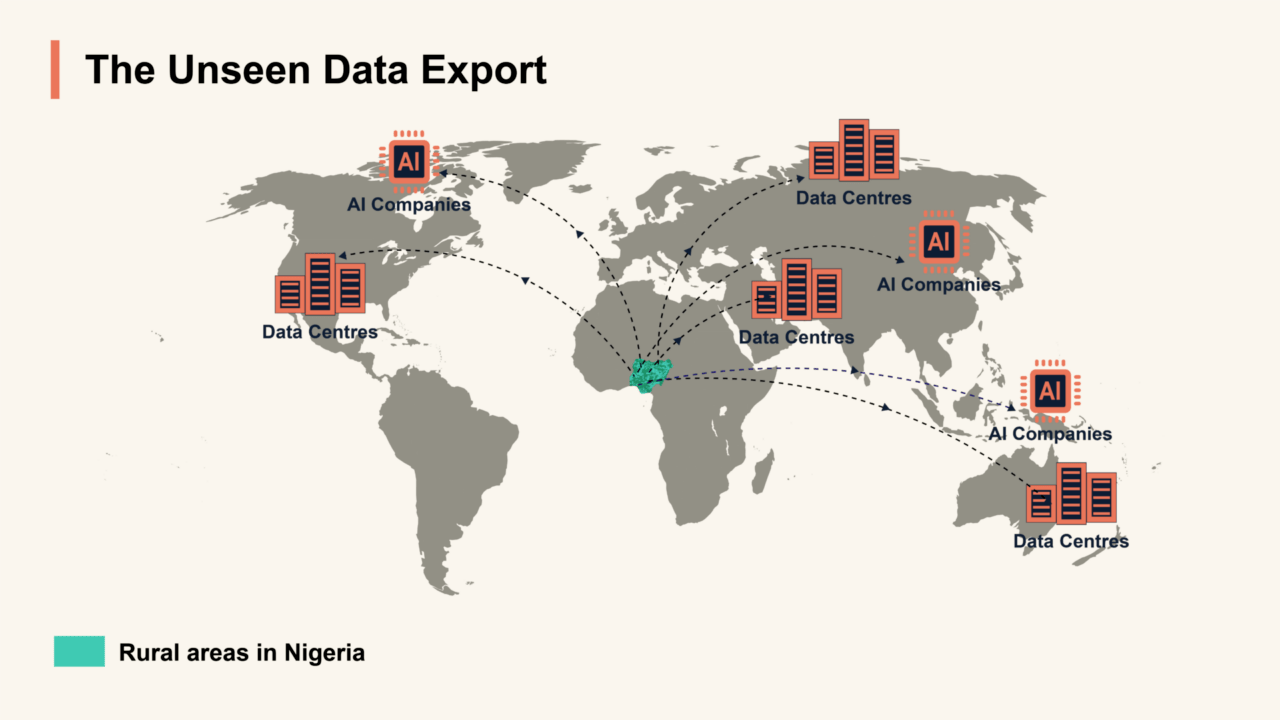

The Invisible Export

The data flowing from places like Kawo in Niger State, Asaeme in Abia State, or Okitipupa in Ondo State is not exclusively used for local scams and identity theft. It is, unfortunately, a raw material powering the global AI economy. Every fingerprint taken for a SIM registration, every blurry ID photo uploaded for a micro-loan application, every demographic detail collected during a census outreach programme, once compromised, becomes a prized commodity on a global black market. This illicit trade operates in plain sight, but remains largely invisible to its primary victims.

Laraba Salisu, a cybersecurity expert based in Minna, refers to this practice as “ethical laundering.” She explains, “Illegally or unethically acquired data from regions like rural Nigeria with weak oversight is anonymized and then sold on dark web marketplaces or integrated into legitimate datasets used by respectable companies. Not many people are aware that foreign AI companies often turn a blind eye to the origins of data, especially if the price is right and the data is untraceable. What this does is that it systematically corrupts the ethics of the AI systems built upon such tainted information.”

The implications are, however, far-reaching. AI systems trained on illicitly obtained data can inherit and sustain societal biases, worsen existing inequalities, and become vulnerable to manipulation or unintended consequences. “If the foundational identity and demographic data of a nation’s citizens are digitally stolen and used by external entities, how can that nation truly control its own digital destiny or hope to build an equitable and independent AI-driven future for its populace?” Salisu asks.

Deception and Disregard

The most common data drain vector, as Mama Khadijat’s experience shows, preys systematically on digital illiteracy and the trust of rural communities. For Nigeria’s rural population, scams often masquerade as urgent notifications for government grants, lottery wins, or routine system updates, all designed to prompt the unsuspecting victim to volunteer sensitive personal information. A recent report by the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) noted a 45% increase in phishing and social engineering attacks specifically targeting rural mobile money users in the last year alone. The collective financial losses from these attacks now amount to billions of naira annually, siphoned silently from the accounts of hardworking Nigerians.

A far more dangerous systemic channel, however, involves rogue agents embedded within legitimate processes. Some mobile network agents responsible for registering SIM cards, census enumerators collecting biodata, and even government officials handling aid distributions, can become unintentional or willing conduits for illicit data harvesting. These individuals, betraying the trust placed in them, might either sell information on the black market or use them for identity theft schemes.

“We have seen cases where SIM cards are registered using stolen identities that were initially obtained through such channels,” revealed a Police Inspector in Lokoja, who requested anonymity to speak freely on the matter. “The initial data point might be collected legitimately, perhaps during a routine registration or survey, but if the local database where it is stored is insecure, or if the person collecting it is compromised and can be bought, that data then instantly enters the black market. Some of the documents we have reviewed from recent arrests confirm this disturbing pattern, showing detailed lists of names, addresses, and National Identification Numbers (NINs) exchanged for ridiculously small amounts of money.”

Is The NDPA a Law Without Teeth?

The Nigeria Data Protection Act (NDPA), which was signed into law in June 2023, established the Nigeria Data Protection Commission (NDPC) and outlined stringent rules for data collection, processing, and protection, mirroring global best practices like Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The Act mandates consent, transparency, and accountability for data handlers, promising heavy fines and even imprisonment for breaches.

“The NDPA is excellent on paper, a huge step forward for Nigeria’s digital ecosystem,” admits Barrister Ufedo Shalom Sanni, a lawyer practising in Abuja. “But laws, no matter how well-crafted, do not enforce themselves. The NDPC, with its mandate to protect the data of over 200 million Nigerians, needs to establish a strong rural enforcement presence. You simply cannot regulate privacy effectively or protect vulnerable populations from an office in Abuja. You need feet on the ground, awareness campaigns, and accessible reporting channels in communities.”

This resource gap manifests in various ways at the operational level. While Nigeria’s 2024 budget does not explicitly state allocations for the NDPC, its parent Ministry of Communications, Innovation and Digital Economy received ₦28.54 billion naira, less than 1% of the total budget.

“When a farmer in Kogi State has their identity stolen and their bank account emptied,” the Police Inspector further explains, outlining the systemic failure, “they report it at the station, as is customary. But we, at the local level, often lack the funds, digital forensics skills, investigative tools, or even basic, reliable internet access to follow up on such cases. These cases rarely even reach the state cybercrime unit, let alone the NDPC.”

The NDPA’s enforcement is also hindered by global jurisdictional challenges. Data harvested in Nigeria can, for instance, be quickly transmitted and processed in data centres in Europe, anonymised further in Asian markets, and monetised by AI companies in North America. Tracing these digital complexities across multiple international borders requires sophisticated international judicial assistance agreements and diplomatic cooperation, which are often slow or non-existent for cases originating from such grassroots cybercrimes. Consequently, the perpetrators remain shielded by geographic distance and legal loopholes.

Erosion of Trust, Loss of Future

These data breaches and scams are systematically eroding the trust essential for Nigeria’s digital transformation. Mr. John Adigun, a recently retired teacher in Oshogbo, Osun State, recounts his near-miss with a similar scam. “I almost had my entire pension details compromised after receiving a fake ‘NIN update’ call,” he recounts. “I initially told the caller to call back, intending to verify. But after talking to a neighbour about the suspicious nature of the call, I quickly realised they were scammers. To think that I almost lost my entire pension makes me so afraid even now. Now, every single time my phone rings with an unknown number, I fear it’s another attempt to steal the little I have.”

“This erosion of trust in digital services is a threat to Nigeria’s digital inclusion agenda. If people, particularly in rural and low-income communities, fear using mobile banking applications or e-governance platforms due to the data breaches and scams, the foundation upon which our AI prospects are meant to be built crumbles,” warns Laraba Salisu, the cybersecurity expert.

This fear results in a cycle of digital exclusion, further marginalising those already underserved, denying them the economic and social benefits that digital access is supposed to provide.

Reclaiming Our Digital Destiny

“The issue of Nigeria’s export of personal data is a serious one,” concludes Salisu. “It demands an urgent, systemic re-evaluation of the NDPA’s implementation strategies, with a particular focus on rural communities. The current approach is simply untenable.”

Hussaini Musa, a Minna-based rights advocate, also believes that the solution lies in a grassroots approach. “Training programs, delivered in local languages through trusted community leaders and local channels, are needed,” Nnaji asserts. “These programs need to clearly explain data rights, teach people to identify and resist digital scams, and outline channels for reporting breaches without fear or delay.”

Mama Khadijat’s experience is a warning that an equitable and advanced digital society can only emerge when the security and dignity of every citizen, from cities to rural areas, are protected. As Musa aptly puts it, “We have to protect the very people our digital plans are trying to benefit.”

This report was produced with support from the Centre for Journalism Innovation and Development (CJID) and Luminate.